Another Look at Red Alder

by Debbie Teashon

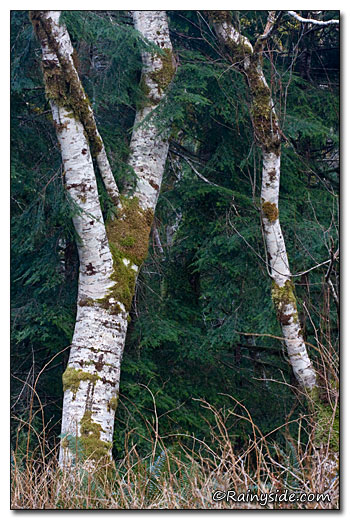

A forest of lichen-covered red alder (Alnus rubra) is a remarkable sight. Peering through a stand of the trees, you can almost see the creatures artists often depict hiding in white-barked trees covered with snow. Because alders are such a common tree in the western portion of the Pacific Northwest, we know them as "weed trees." I know these pioneering natives are prolific anywhere the ground is hospitable for their seeds, especially as I'm pulling numerous alder seedling volunteers out of my ornamental gardens and near my fruit trees year after year. Whenever I see a beautiful stand of our native trees, my grumbling quickly stops.

Ecologically red alders are essential for many reasons. They fix nitrogen into the soil — well, not exactly. If you pull up an alder seedling, you'll see nitrogen-filled orange-red nodules all over its roots. What happens is that a bacterium called actinomycete invades the tree's roots, where it draws nitrogen from the air and fixes it to the roots. In the Northwest, red alders provide a great way to get the nitrogen back into the soil, which our rains wash away. A stand of these trees can provide up to 705 pounds (320 kg) of nitrogen every year! Red alders grow in avalanche tracks, flood plains and other disturbed areas, such as where logging occurred. The trees help provide nitrogen for young conifers growing up under the vital protection of their canopy. Red alders begin their decline at the age of 50, giving way to the next generation of forest trees, which have grown up under their care.

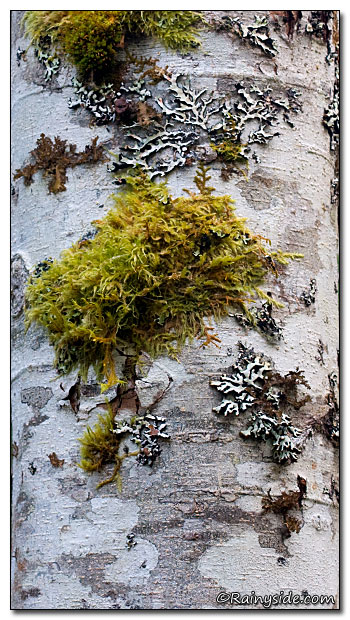

Epiphytic lichen (which grows on trees) covers the bark with mosaic patterns of white and gray with tinges of light pink, making the alders look like birch trees.

One type of lichen that grows on alders is commonly called pencil script lichen (Graphis scripta), an ancient species dating back at least 25 million years. This lichen is white with black fruiting bodies that resemble tiny hieroglyphs drawn in pencil. Alder bark is one of its favorite hangouts.

Have you ever wondered why you saw barnacles growing on an alder tree? They are not barnacles but fruiting bodies of the bark barnacle lichen (Thelotrema lepadinum). Underneath the lichen, the bark is brown. Where the air is free of pollutants, the lichen freely covers the bark as the tree grows. In areas where pollution is severe, the lichen will die off — a good air quality indicator.

Our native tree grows exclusively west of the Cascades between Alaska and California, except for a few isolated stands in Idaho. You can also find the alder growing in Hawaii, where it was introduced for cultivation. Before settlers came to the Northwest region, the species preferred growing alongside streams and wet areas. However, with our expanding population and the logging industry's clear-cutting practices, the tree is now plentiful throughout the region.

Alder is our most abundant hardwood, used for making fine furniture and cabinets around the world. Considered the best wood for smoking salmon, the Salish and coastal tribes once ate the inner bark of alder, scraping it off in the spring, mixing it with oil, or drying it in cakes for winter use. Clothes, utensils, dyes, and medicines also came from the alder.

The next time you look at a red alder tree, consider all its symbiotic relationships and its usefulness. It is a fascinating tree and much more helpful to be considered a weed.

USDA zones 6-8.

Sunset zones 4-6, 15-17.

Gardening for the Homebrewer: Grow and Process Plants for Making Beer, Wine, Gruit, Cider, Perry, and More

By co-authors Debbie Teashon (Rainy Side Gardeners) and Wendy Tweton